| Center City Commuter Connection (Commuter Tunnel) |

Links to article sections:

Commuter Tunnel Overview

Reading Terminal and Market East Station

Concept of Commuter Tunnel

Early Planning for Commuter Tunnel

Mayor Frank Rizzo's Influence on Commuter Tunnel Project

William Coleman Approves Federal Funding for Commuter Tunnel

Design, Construction and Operation of Commuter Tunnel

Market Street East Redevelopment Area and the Gallery

Links

Sources

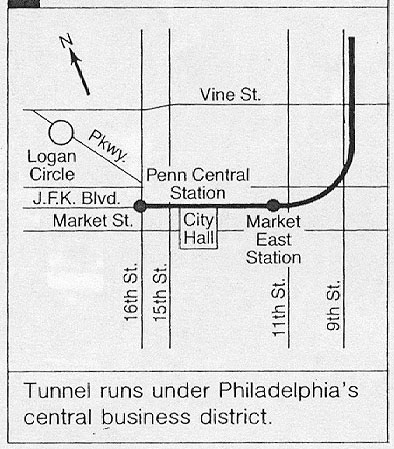

The Center City Commuter Connection (CCCC), commonly known as the Commuter Tunnel, was opened in November 1984. It connected the two downtown Philadelphia commuter rail stations, the Suburban Station (Penn Center Station, ex-Pennsylvania Railroad) and the Reading Terminal (ex-Reading Railroad). These two commuter rail systems each formerly ended at downtown stub-end terminals. The Suburban Station is located at 16th Street and J.F.K. Boulevard, and the Reading Terminal was at 12th Street and Market Street. The Commuter Tunnel was first proposed in 1958, and was for many years a dream that many thought would not come to pass. Construction was started in 1978, and was completed in 1984, and it cost $330 million. The CCCC belongs to the City of Philadelphia, and the project received 80% federal funding from the Urban Mass Transit Administration (UMTA) which is now named the Federal Transit Administration (FTA).

From John Hay of Philadelphia - Ground was broken for the project on June 22, 1978; real work got underway quickly. The CCCC was fully opened on November 10, 1984; a Market East-Suburban Station shuttle began operation on June 7 of that year, after which Paoli and Chestnut Hill West trains were extended to Market East. It was far from on-schedule. According to Railway Age magazine in 1978, completion was originally scheduled for 1981. Serious delays were incurred, not on construction of and in the tunnel itself, but in finishing connecting trackwork, interlockings and signaling due to the exit of Conrail from commuter rail operation, and on the power supply due to a City-Federal-Amtrak squabble over whether to use 11 kV or 25 kV. (Amtrak has always supplied the 11 kV power in the tunnel, even though the City owns the catenary and substation, and SEPTA runs all trains). SEPTA's dearth of qualified engineers for its trains after Conrail left also delayed opening by over half a year. All this also inflated costs somewhat, mainly due to national inflation.

The tunnel is 1.7 miles (2.7 km) long. The Suburban Station is underground at Penn Center, and the new tunnel extended eastward from there, passing above the north-south Broad Street Subway, passing just north of City Hall, passing in tunnel by the elevated Reading Terminal, curving to the north, passing under the Ridge Avenue Subway, and gradually ascending to grade, and connecting to the existing elevated Reading line at the north edge of Center City.

The Penn Central Railroad (formed in 1968 by the merger of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad) and the Reading Railroad, went out of business in April 1976 when they were absorbed as part of the federally-assisted Conrail system.

Near the Reading Terminal (now the Pennsylvania Convention Center and Hard Rock Cafe) is the new Market East Station. The $75 million Market East Station is the centerpiece of the whole project, and it was designed as a huge atrium so that daylight filters down to the track level 35 feet (10.7 meters) below the street. The station is 120 feet (36.6 m) wide and two blocks long. Passenger access is accomplished with escalators, elevators, and provisions for the handicapped. There are extensive telephone, radio and TV surveillance systems in place, and there is a computer operated arrival and departure system with CRT displays to help guide patrons to the correct trains. The Market East Station is within a block of the Reading Terminal, and it replaced the elevated Reading Terminal, since the new CCCC tunnel passed far below the elevation of the original terminal.

Sandy Smith, "Exile on Market Street", Philadelphia - The Reading Terminal opened in 1893, and replaced a farmers' market that operated on the site of the headhouse-but the trainshed is now the Great Hall of the Pennsylvania Convention Center and the headhouse is now being rebuilt as an addition to the Marriott Hotel across 12th Street (which is connected to the terminal building by a pedestrian bridge). It is now once again possible to enter Market East Station through the Reading Terminal headhouse. A new entrance lobby officially opened in March 1998; the lobby provides direct access from Market Street to both the rail station and the Great Hall. Murals at the Great Hall level (facing the trainshed) depict classic Reading Railroad locomotives.

The Market East Station is integrated with the Gallery, which is a huge 5-story retail complex. John Hay of Philadelphia - The Gallery is a complex of department stores, retail shops, and food courts. The Aramark office tower next to the Terminal was also contemporaneous with the Gallery II and the CCCC.

By the time that the construction began on the Commuter Tunnel, the Reading Terminal was in poor physical condition and would have required expensive renovation had it not been replaced.

When I lived in the Philadelphia area in the 1970s, a large area between City Hall and the Delaware River, generally along Market Street, was designated as the Market Street East Redevelopment Area, and construction of the Gallery started. A massive amount of office, commercial and hotel development has taken place since then, and the Market East Station is a linchpin. The station and surrounding development is also integrated with the Market Street Subway by connecting underground concourses.

The concept behind the Commuter Tunnel was to connect the two commuter rail systems in the downtown, to allow through-routing of commuter trains, and to eliminate the capacity limitations and operational difficulties imposed by stub-end terminal designs. From what I gather, not much passenger traffic goes "through the tunnel", i.e. completely through all three Center City stations. The main benefit of the tunnel is that much more capacity exists in the corridor, and that commuters on either the ex-Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) or ex-Reading Railroad system have three downtown stations for distribution. Formerly, PRR commuters had two downtown stations, and Reading commuters had only one. Note here that when I mention a third major commuter train station, I am referring to 30th Street Station, which is technically not in Center City, but right across the Schuylkill River at 30th Street and Market Street. 30th Street Station is the huge train station that sits astride the Northeast Corridor railroad mainline, and it has a lower north-south concourse for Amtrak intercity trains, and an upper east-west concourse for PRR system commuter trains heading to and from the Suburban Station and points east. The Commuter Tunnel actually extended the existing 6-block commuter train tunnel that runs east-west from 22nd Street to the Suburban Station at 16th Street. So the entire old and new Commuter Tunnel combined is actually almost 2.5 miles (4 km) long, right through the heart of Center City Philadelphia.

The Commuter Tunnel does much more than just connect the two formerly stub-end terminals, which by itself was a first for any U.S. city. It provides the region's 5 million people with through service on 13 commuter rail lines covering some 500 miles, joined by underground pedestrian concourses to the city's network of subways, trolleys and busses. The Market East Station is a major transportation center as well as the centerpiece in massive urban renewal east of City Hall.

Trains going through the connecting part of the Commuter Tunnel (between Market East Station and Suburban Station) carry significant number of passengers, such as workers headed to west side office buildings and shoppers and tourists heading to east side stores. Many college students use the linked system to get home on weekends.

In the decade before the Commuter Tunnel opened, the Market Street East redevelopment construction included two department stores, Galleries I and II, which are among the most successful urban shopping malls in the country, and two large office buildings. These buildings were all designed for access to the then-unbuilt Market East Station. Major additional development has followed since the tunnel opened.

Ridership on the regional commuter rail system increased to about 85,000 daily right after the tunnel opened, up from 72,300 just before. In July 1985 when ASCE wrote its feature article about the Commuter Tunnel, they reported that the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) would spend several hundred million dollars in the five-year period after the tunnel opened, to provide necessary improvements to the regional commuter rail system. This would include upgrades to tracks, power distribution and signal systems, as well as major bridge repairs and 72 new rail cars. The future proved somewhat different. John Hay of Philadelphia - All 232 Silverliner IVs arrived between 1974 and 1977. The next new equipment came in 1988, in the form of 7 AEM7 electric locomotives and 35 push-pull coaches. These last finally retired the "Blueliners" as well as the nonstandard Pioneer III Silverliners. The Tunnel was shut down north of Market East on 11-16-84, less than a week after opening, when a bridge at Temple University station was found to be in imminent danger of collapsing. The USACE built a temporary bridge within a month, so that full service could resume in December 1984. This incident led to the massive RailWorks® project which rebuilt the Ninth Street Branch (the SEPTA mainline) between the tunnel and Wayne Junction in 1992 and 1993, in which 20 bridges were replaced, 5 rebuilt, track, signals and power were totally redone, and a new Temple station was built in a new location.

On April 28, 1985, a new commuter rail line was opened to Philadelphia International Airport (PHL). It is about 7 miles (11.3 km) long, and was built partially along the existing Northeast Corridor Philadelphia-Wilmington mainline, and partially on new alignment, with a long curving bridge over Bartram Avenue, Interstate 95, and Industrial Highway, ending in a series of 4 stations at the airport. This line was integrated with the post-tunnel regional rail system, and provides direct service from Center City to the airport.

The University City Station was built at the University of Pennsylvania and it opened in 1995, and the existence of the Commuter Tunnel helps its patronage.

I lived near Philadelphia in the 1970s, and I read newspaper articles about the planned project. There was talk about rerouting Amtrak intercity trains through the tunnel, right through the heart of Center City, but I don't think that will come to pass. George Scithers of Philadelphia - The only way that Northeast Corridor trains could be routed through the tunnel on their way between Washington and New York, would be to build a connection between the ex-Pennsylvania and ex-Reading Company lines in the vicinity of (but bypassing) the old North Philadelphia station- and the price tag on such a connection was almost as much as the cost of the CCCC.

Early Planning for Commuter Tunnel

There had been talk for decades about building some kind of railroad link between the downtown terminals of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) and the Reading Railroad, and in 1958 the idea finally went beyond talk. Philadelphia Mayor Richardson Dilworth ordered the city Planning Commission to prepare a plan to revitalize the decaying Market Street East area. This portion of the downtown had been the region's commercial center, with three large department stores around Eighth and Market Streets, but the area started to decline substantially after World War II, when many families began moving to the suburbs and began doing most of their shopping in the new shopping centers and malls in the suburbs.The Market Street East redevelopment plan included a tunnel link between the two commuter rail stations, as an integral part of the plan. The tunnel was immediately given a high priority by Mayor Dilworth, as he accepted the concept soon after he heard about it. This gave the project viability, and it also received immediate support from the city's business community. City leaders and the business community saw the tunnel as a way to attract new retail and office development to the Market Street East area. The cost estimate for the tunnel in 1958 was $28 million, and the plan was to fund the project with state and local tax funds with some help from the railroads.

This 1958 tunnel link proposal included a new commuter rail station called the 11th Street Station which would be located underground at 11th and Market Street, and the basic concept from then until the Commuter Tunnel was built, was to keep the Suburban Station in service, extend the underground railroad line eastward from there, passing just north of City Hall, passing in tunnel by the elevated Reading Terminal, curving about 90 degrees to the north, gradually ascending to grade, and connecting to the existing elevated Reading Company line at the north edge of Center City near Spring Garden Street. The Reading line south of the new north connection would be abandoned, and the Reading Terminal would be closed to train service. The 11th Street Station was later renamed the Market Street East Station, with the name changing again to Market East Station before it opened to service, with the last name being the name since then.

The two railroads were not very enthusiastic about joining their two Philadelphia

area commuter rail systems. The two railroads had engaged in intense competition

in the coal transportation business for decades, as Pennsylvania has large amounts

of coal in its land. There was not much competition for commuters, although the

two railroads did operate parallel commuter service to the Chestnut Hill section

of northwest Philadelphia, which is one of the more exclusive sections of the

city. James M. Symes, chairman of the board of the Pennsylvania Railroad, was

quoted as saying in 1962, (from Mass Transit magazine, April 1979

article, in blue text):

The railroad officials had another major objection to the commuter tunnel.

They didn't think that it would work operationally. The above article also cites

another well-known quote, also cited in the book The Wreck of the Penn Central.

I'll repeat it here, from Stuart T. Saunders, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad

/ Penn Central Railroad in the 1960s (blue text):

The cite refers to the original multiple-unit PRR and Reading commuter rail cars, some of which were painted on the exterior with red, and some with green; some built as long ago as the 1920s. I rode on some of these on the Paoli Local when I lived in the western suburbs of Philadelphia in the 1970s, and they were indeed old, well-worn cars that had very slow acceleration. Some Philadelphia railroad buffs disagree with the assertion that the old cars couldn't make it up a 2 percent grade after starting from a level stopped point, three blocks from the grade. It is a moot point, since by the time that Commuter Tunnel construction began in 1978, most of the old cars had been replaced by the newer Silverliners. The higher-performance Silverliners went into PRR and Reading commuter service in phases in the late-1950s, 1960s and 1970s. These cars were used in the Commuter Tunnel after it opened, and they can make it up the steep grade with ease (actually 2.8 percent at the steepest, which is steep for a railroad).

I asked Matthew Mitchell of the Delaware Valley Association of Rail Passengers, the above question, "Some Philadelphia railroad buffs disagree with the assertion that the old cars couldn't make it up a 2 percent grade after starting from a level stopped point, three blocks from the grade". Matthew replied, "Well the Blues would grind their way up, but they made it just fine, and they always sounded like that". So according to him, the older rail cars could successfully utilize the commuter tunnel.

When it became clear that the railroads couldn't be expected to provide any funding to build the commuter tunnel, city officials began looking elsewhere. In July 1964, the U.S. Congress created the forerunner to UMTA (U.S. Urban Mass Transit Administration, today's Federal Transit Administration). City officials quickly prepared an application for a capital grant for the tunnel, and submitted it to UMTA in November 1964. City Mayor James H.J. Tate optimistically predicted that construction would begin in 1966. Unfortunately for Commuter Tunnel project advocates, it would be 11 years before UMTA finally agreed to provide funding to build the tunnel. As an interesting aside, this application for federal funds for the Commuter Tunnel was the first application for capital funds received by the newly formed UMTA, then known as the Federal Office of Transportation in the Housing and Home Finance Agency.

The initial answer by UMTA was that they viewed the tunnel as an urban renewal project, and not as a transportation improvement. The city argued that the two functions could not be separated. In 1970, UMTA concluded in an official report, "The benefits to the Philadelphia area mass transportation system resulting from the center city project are, at best, minimal".

Mayor Frank Rizzo's Influence on Commuter Tunnel Project

In 1972, a new person entered the Commuter Tunnel saga, one who many Philadelphians credit as being the most important person in providing the leadership and lobbying to secure the necessary funding and political commitments needed to begin construction of the Commuter Tunnel. This was Mayor Frank L. Rizzo, the former city police commissioner, who became mayor in 1972 and served two consecutive four-year terms. He was a rather outspoken and controversial mayor, and was the target of an attempted movement to recall him (dismiss from elected office) in 1975. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court stopped the city-authorized recall process as being un-Constitutional, after sufficient petition signatures had been obtained to force a recall election, but before a recall election could be held. Rizzo had quite a few critics, but he had many supporters also, and quite a few people today would credit him as having gotten a lot accomplished in the city during his terms.

Rizzo's staff helped convince him that the Commuter Tunnel could become his legacy to the city, and he made the tunnel the region's top transportation priority, even though this meant delaying other major transit projects such as the replacement of the old Broad Street Subway cars.

I rode the Broad Street Subway (BSS) at times in the early- and mid-1970s, and the cars were very old with slow acceleration. The Broad Street Subway opened between City Hall and Olney in 1928, and the first fleet of BSS cars date from that time. Additional BSS cars were received in 1938. The "Bridge Cars" to Camden were delivered in 1936. The new BSS Kawasaki cars were delivered in 1982-83. As an aside, the Market Street Subway-Elevated line was opened in 1907 and extended to Frankford in 1922; new cars were delivered in 1960, and that fleet was replaced in 2000.

Many city residents disagreed with Rizzo's priority on the Commuter Tunnel, and saw it as something that would primarily benefit Center City businessmen and suburban commuters, while many working class parts of the city still had old buses in use, and the Broad Street Subway car replacement project was seen by many people as having much greater impact on the city's neighborhoods. This viewpoint ignored the fact that a considerable portion of the PRR and Reading commuter rail system was within the city, including several dozen stations. Also, the commuter rail connection to Philadelphia International Airport was in the planning stages at the same time (it was completed in 1985), and as a part of the commuter rail system (and not the subway/elevated system), the Commuter Tunnel would provide a direct connection and better access between the Reading system commuter stations in the city and the airport (the airport line would extend from the PRR system just south of 30th Street Station). All commuter rail stations inside and outside the city would be joined into one system by the Commuter Tunnel, and linked to the airport too when that line opened; so it is simply false to suggest that the Commuter Tunnel would only benefit Center City and the suburbs, since the tunnel would also provide a major mass transportation improvement to most of the City of Philadelphia.

The estimated cost of the Commuter Tunnel in 1972 was $200 million. The city proposed to provide $37 million of that from city tax funds, and many people in the city's blue-collar neighborhoods resented that. Even with Rizzo's support, the application for federal funds still languished in Washington. John Volpe, U.S. Secretary of Transportation, said to the city officials in 1972, that there was a "slim chance that the tunnel would ever get federal money because the $200 million that was then the estimated cost could be better spent on other transit projects". Volpe did later authorize $4.1 million for a grant for a technical and economic study about the Commuter Tunnel, and that was encouraging for the project's backers.

In 1974, UMTA expanded the scope of its policies to allow the agency to participate in the transit-related aspects of urban renewal projects. The Rizzo administration immediately used that angle to pressure the new U.S. Secretary of Transportation, William T. Coleman, himself a Philadelphian, to approve the 10-year-old application for federal funds for the Commuter Tunnel. Coleman himself had reservations about the project and its escalating cost estimate, then $307 million ($240 million requested from UMTA, $30 million from the state of Pennsylvania, and $37 million from the city). Coleman was quoted in late 1976,

"I know a lot of people want the tunnel built. But I am not sure it is the best way of transporting people. It is a heck of a lot of money to spend for 1.7 miles of track."William Coleman Approves Federal Funding for Commuter Tunnel

William Coleman also expressed a concern that halfway through construction, that Philadelphia would come back to UMTA and say that the costs were higher than expected, and would ask for more money. He suggested that the city abandon the project, and use the requested $240 million in federal funds for other transit improvements, reflecting the argument that several neighborhood groups were making at that time. Mayor Rizzo still insisted that he wanted the Commuter Tunnel built. Then over a period of weeks, Coleman held discussions with John Bunting, chairman of the board of First Pennsylvania Corporation and one of Philadelphia's civic leaders and a tunnel opponent. They both reviewed the tunnel project, and looked at alternatives, and both of them changed their views to support of the tunnel project. Following is a Bunting quote from the Mass Transit article.

"At the time (late 1976) Mr. Coleman did not feel that this was the best way to spend money in the City of Philadelphia on transportation," Bunting said. "But in the subsequent weeks, as we looked over the alternatives, each of us individually and then got together on the matter, both of our views changed. I think first and foremost Philadelphia's needs for spending were tremendous. Philadelphia needed an injection of money and needed it fast. The second reason: There was no other project of comparable impact on the economy of Philadelphia that could be funded in any way and get the money here as rapidly as this one. A third reason was that virtually all the money would be spent here. Other projects involved the purchase of cars and buses. That would have been peachy for Detroit and Canada where those cars and buses were to be constructed. It would not have been so nifty for Philadelphia. Finally, we both felt that in the years that we formed our opinions, which were at one time contrary to the tunnel, the oil crisis in the United States had erupted and had given a much higher priority to a mass transportation project of this sort".

In January 1977, U.S. Secretary of Transportation William Coleman left office along with the outgoing President Gerald Ford administration, and a few days before he left office, he made final decisions on two controversial metropolitan transportation projects that had been elevated to his level to decide on, yes or no as far as receiving federal funding from U.S. DOT. One of these was the Commuter Tunnel in Philadelphia, and the other was the Interstate 66 extension in Northern Virginia from the I-495 Capital Beltway to the I-66 Theodore Roosevelt Bridge (over the Potomac River) into the District of Columbia. Coleman approved both the I-66 extension and the Commuter Tunnel. For the details of the I-66 extension and details about how Coleman handled that decision, see my website article

Interstate 66 and Metrorail Vienna Route. When the incoming Jimmy Carter Administration came into office, his U.S. Secretary of Transportation Brock Adams could have ruled again (yes or no) on each of these projects, but he let both of Coleman's decisions stand in their entirety.Coleman attached conditions to his decision, in that Philadelphia must attract more developers to the Market Street East area, especially in the area near the Commuter Tunnel's Market East Station at 11th and Market Street. Mayor Rizzo was jubilant at the UMTA federal funding agreement contract signing meeting with Coleman, and Rizzo predicted that construction would begin by summer 1977, but three weeks after the signing there was another major delay, in the form of a lawsuit filed in federal district court by a citizens group who wanted to permanently stop the project. The plaintiff was a coalition of community groups who had been long opposed to the tunnel project, on the grounds that the money should be spent on other mass transit improvements in the city. City officials decided to wait for the resolution of the lawsuit, before awarding any construction contracts. Over a year later, in May 1978, Federal District Court Judge Raymond J. Broderick dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that UMTA had properly awarded the City of Philadelphia the 80% federal funding to build the tunnel, and that the whole federal process used to approve the project was in compliance with federal law. Mayor Rizzo held the official Commuter Tunnel construction ground breaking ceremony on June 22, 1978, and proclaimed it "the greatest day in the history of Philadelphia". Rizzo was the mayor during the five years that I lived near Philadelphia, and I can testify to the fact that Rizzo had the ebullient personality depicted here (critics might have called it "bombastic").

Design, Construction and Operation of Commuter Tunnel

The mainline of the Commuter Tunnel is comprised of a four-track reinforced concrete box tunnel. It weaves both above and below pre-existing subway lines, and its design and construction were both very challenging. This included extensive underpinning of the Reading Terminal Train Shed while it was still in use, also extensive underpinning of several historic and high rise buildings along the route. There was massive relocation of utilities, all of which had to be kept in service without disruption. Complex, detailed construction scheduling was needed to maintain motor vehicle, pedestrian and rail traffic at street level, and also in the multiple levels of subways and concourses. The design of the project included plans for interfacing to future buildings.

The design of the Commuter Tunnel needed to prevent train noise and vibration from disturbing downtown buildings and their occupants. The tracks use continuously welded rails which lie on specially cushioned concrete ties. The concrete tunnel structure itself is isolated from adjacent buildings by a two-inch layer of cork. Track level insulation and acoustic panels between tracks deaden noise, and there is no roar or clickity-clack of trains. Overhead electric catenary lines supply power to the trains, all of which are electrically powered.

It was necessary to underpin 12 building structures during the cut-and-cover tunnel construction. Multiple concrete filled, hand dug piers were the normal underpinning technique. However, the 14-story City Hall Annex needed special treatment, because one track of the tunnel box passes directly underneath the building's columns along Filbert Street. The Masonic Temple, constructed in the 19th century, was one of the greatest challenges for the contractors and engineers; a different, stronger underpinning method was used when cracks started appearing in the ornately decorated interior plaster. The elevated Reading Terminal Train Shed is a registered National Historic Engineering Landmark, and it presented special challenges because full train service had to be maintained throughout the construction of the Commuter Tunnel underneath, with extensive underpinning required.

Philadelphia has four subway lines that pass through Center City, and three interfered with tunnel construction at several places. The north-south Broad Street Subway was built in 1928, and it was designed to allow a future subway line to pass over it near City Hall. Clearances were barely adequate for the Commuter Tunnel, and the 120-foot (36.6 m) wide subway roof was demolished and the tunnel was built while subway traffic was maintained on at least two of the four tracks. Just east of the Broad Street Subway, a 400-foot (122 m) section of underground trolley tunnel was parallel to the Commuter Tunnel, and it needed to be moved 16 feet (4.9 m) to the south, without disrupting regular trolley schedules. This is the Market Street Subway-Surface light rail line tunnel that makes a long loop around City Hall. When cut-and-cover tunnel construction passed under a street, the heavy downtown motor vehicle traffic was carried on timber beam decking, which provided a temporary street roadway.

The Commuter Tunnel construction did disrupt Chinatown, where the tunnel turns to the north. The city and contractor project engineers worked closely with the residents and business owners to solve ongoing problems, which included business disruption, parking problems, noise, dust, and traffic flow. The Chinatown Station of the Ridge Avenue Subway lay directly in the path of the Commuter Tunnel, and it had to be demolished and rebuilt on top of the new Commuter Tunnel. This point under the new Chinatown Station at Vine Street and 9th Street is the lowest point on the Commuter Tunnel, about 20 feet (6.1 m) below sea level.

Finally, the grade of the Commuter Tunnel gradually rises as it heads north, and the 4-track tunnel reaches a portal as it comes to the surface, and the roadbed rises onto an embankment, and connects into the existing elevated ex-Reading Company line, on a direct continuous high-speed alignment. John Hay of Philadelphia - This rise is the steepest grade on the SEPTA RRD: 2.8%. The west end connection of the Commuter Tunnel was a bit easier, since the underground Suburban Station ended at a concrete wall. The wall was removed, and the tunnel built eastward. George Scithers of Philadelphia - There was more work on the old Suburban Station: the four through tracks are on the south side of the station, while, as built, the station was designed for two tracks on the north side of the station eventually to be extended eastward toward a possible tunnel under the Delaware River to connect to the then-electrified Pennsylvania lines out of Camden NJ. In order to provide adequate platform space in Suburban Station, two then-existing tracks were taken out of service and replaced with widening of the adjacent platform. Each of the two island platforms on the through tracks is now about double its previous width.

Complex, detailed coordination during construction was required to maintain motor vehicle, pedestrian, trolley, and underground rail traffic. The design of train operations was complex, because the project design was begun in the 1970s when the transition from private ownership of the railroads to SEPTA administration was taking place. Construction management was very challenging, as there were 46 different construction contracts to manage and keep on schedule while maintaining their independent critical paths. Overall project construction management was preformed by a joint venture of three civil engineering firms, called CM Philadelphia Railway Consultants. Duties included administration, quality assurance, design support, and project documentation.

Center City Commuter Connection - Line Operations - my article with details provided by Matthew Mitchell of the Delaware Valley Association of Rail Passengers, with more information about the Commuter Tunnel and the Philadelphia regional commuter rail system.

Market Street East Redevelopment Area and the Gallery

After World War II, there was a major business and residential decline in the area of Center City Philadelphia in the Market Street area east of City Hall. Market Street is the major east-west thoroughfare that runs through downtown Philadelphia and West Philadelphia. Philadelphians commonly refer to downtown Philadelphia as "Center City". Center City includes not only many large retail and hotel businesses, historical sites, and major city government offices, but also over 60,000 residents in homes and apartments. The most commonly recognized boundaries of Center City, are the Delaware River and the Schuylkill River on the east and west respectively, and Spring Garden Street and South Street on the north and south respectively.

The Market Street East area was once thought by many to be beyond help. Philadelphia's business and political leaders combined urban renewal and mass transit improvements, and were able to renew this area from 1973 onward. The business linchpin of this renewal is the Gallery, which is a huge 5-story retail complex of department stores, retail shops, and food courts. The Rouse Company had developed many suburban malls, and in 1973 they proposed building an enclosed mall in Center City near the intersection of 9th Street and Market Street. Skeptics predicted that it would fail, but Rouse Company executives said that it would be a success because of its downtown location near the hub of Philadelphia's rail transit system, with three systems all having a station at 8th and Market streets; these systems are the Market-Frankford Subway-Elevated, the Broad Street Subway (Ridge Avenue Spur), and the Lindenwold High Speed Line (PATCO). The proposed commuter rail Market East Station at 11th and Market streets was on the horizon, and with the Commuter Tunnel joining the PRR and Reading commuter rail systems, would provide a downtown station of a fourth rail system within two blocks of the new urban mall.

The Gallery opened on August 11, 1977, and it was a success from the day it opened, with nearly 100 percent occupancy. Its lowest level is at subway level, with a level at street level, with the highest level several levels above street level. It had 125 shops and restaurants, with a new Gimbels department store anchoring one end of the mall, and an extensively renovated Strawbridge and Clothier department store anchoring the other end of the mall. A survey taken 18 months after the Gallery opened, showed that 68 percent of the customers and almost 100 percent of the employees, used public transit to get there, primarily on the three rail systems.

After the Commuter Tunnel federal funding agreement was reached between UMTA and the City of Philadelphia, the Rouse Company began studies on extending the Gallery eastward along Market Street and building directly over the new Market East Station at 11th Street. The synergy of the Commuter Tunnel and the Market Street East business developments, helped spur and support the development of each. Gallery II opened in 1983, with another shopping mall with a department store and twin office towers. So it can be seen how the combined efforts of business executives, city officials, and state and federal officials, worked together over a period of many years to revitalize the Market Street East area and bring about business and transportation expansion to the area, and these efforts have created a lot of urban vitality.

Looking from the mezzanine to the track level in the new Market East Station.

Taken by Scott Kozel in 1985 soon after opening. The tunnel has four tracks throughout.

You can see glimpses of the third and fourth tracks at the edge of the picture.

The Philadelphia Center City Commuter Connection (CCCC), commonly known as the Commuter Tunnel, was elected the Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement for 1985 by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). ASCE Website - Founded in 1852, ASCE represents more than 120,000 civil engineers worldwide, and is America's oldest national engineering society.

Center City Commuter Connection - Line Operations - my article with details provided by Matthew Mitchell of the Delaware Valley Association of Rail Passengers, with more information about the Commuter Tunnel and the Philadelphia regional commuter rail system.

SEPTA Trains - history

and photos by the Philadelphia Transportation

Page. Also

New Jersey Transit. Excerpt from SEPTA Trains (blue text):

The Southeastern Pennsylvania

Transportation Authority (SEPTA) provides train service over thirteen commuter

rail lines in Philadelphia's northern and western suburbs (and to the airport).

With the exception of the Airport Line, SEPTA’s commuter rail lines were all formerly

operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad or the Reading Company. Prior to 1984, the

former Pennsylvania lines converged at 30th Street Station, and continued to Suburban

Station, which was their Center City terminal. The former Reading lines used Reading

Terminal as their terminal. The Center City Commuter Tunnel connected the two

systems in 1984, using a new section of tunnel and a new station (which replaced

the Reading Terminal) beneath Center City. Most trains now use the tunnel to run

from the Pennsylvania side through to the Reading side, which allows for greater

efficiency.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Regional Rail - history and photos (2 photos of the Market East Station) by Jon Bell. Philadelphia Transit Links and Jon Bell's (Mostly) Rail Transit Pages.

Philadelphia: Regional Rail Lines - history and photos by www.nycsubway.org. Includes narrative on The Center City Tunnel and Approaches.

SEPTA (Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority) has a webpage with links to SEPTA Regional Rail Schedules. Each line has a page with the schedule and a map. SEPTA Railroad and Rail Transit Map.

1. "The Tunnel That Transformed Philadelphia", Civil Engineering/ASCE

magazine, July 1985.

2. "Philadelphia Finally Gets its Tunnel", Mass Transit magazine,

April 1979 article, by David C. Hackney, transportation reporter for the

Philadelphia Bulletin. The Philadelphia Bulletin was

the major evening newspaper for the Philadelphia area from 1847 to 1983.

3. The Wreck of the Penn Central, by Joseph R. Daughen and Peter

Binzen, 1971.

4. Several railroad history buffs from Philadelphia - Sandy Smith, John Hay, and

George Scithers; their comments after review of the first draft are shown in

italics.

Copyright © 1998-2003 by Scott Kozel. All rights reserved. Reproduction, reuse, or distribution without permission is prohibited.

By Scott M. Kozel,

PENNWAYS(Created 5-26-1998, expanded 9-28-2001, updated 10-14-2003)